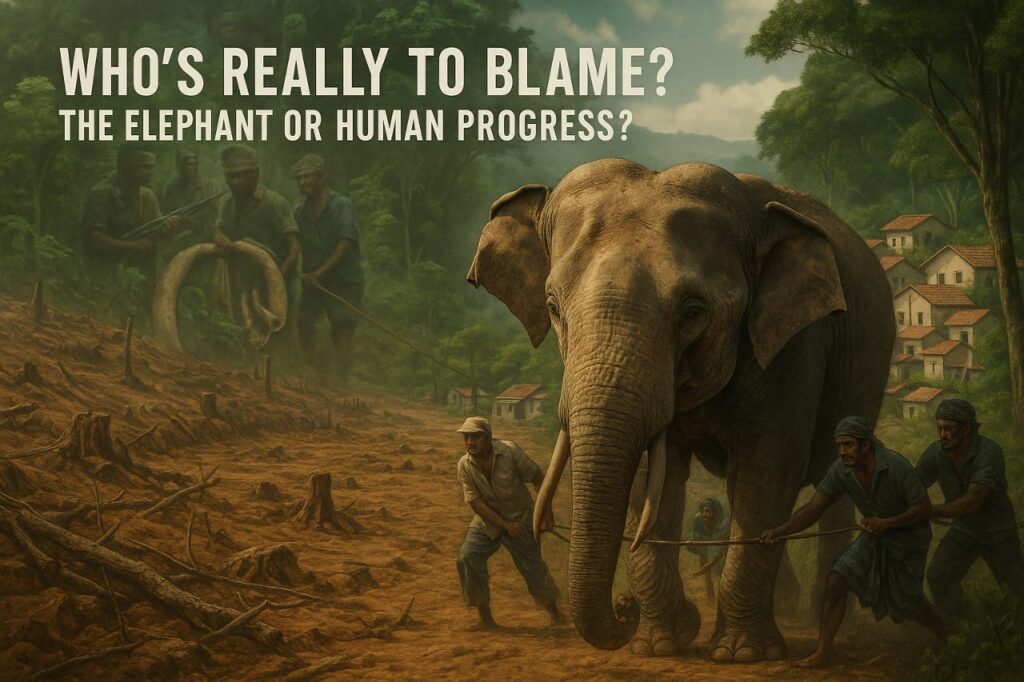

The Sri Lankan elephant (Elephas maximus maximus), the largest and darkest of the Asian elephant subspecies, is an iconic symbol of Sri Lanka’s rich biodiversity and cultural heritage. Revered in religious festivals like the Esala Perahera and historically significant for their role in logging and warfare, these majestic creatures face an uncertain future. With a population decline of approximately 65% since the 19th century, the Sri Lankan elephant is now classified as endangered. The primary threats are habitat loss, fragmentation due to human encroachment, and escalating human-elephant conflict (HEC). This article delves into the challenges faced by Sri Lankan elephants, supported by key statistics, explores government conservation strategies, and examines efforts to raise public awareness to foster coexistence.

The Scale of the Crisis: Key Statistics

The Sri Lankan elephant population has plummeted from an estimated 19,500 at the beginning of the 19th century to approximately 5,879, according to the 2011 census by the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC). Some conservationists suggest the current number may be closer to 4,000 due to ongoing habitat loss and high mortality rates. Sri Lanka hosts about 10% of the global Asian elephant population, despite accounting for only 2% of their range, making it a critical stronghold for the species.

Human-elephant conflict is a severe issue, with Sri Lanka recording the highest annual elephant mortality rates globally and the second-highest human deaths due to HEC, after India. Since 2019, an average of 370 elephants and 125 humans have been killed annually due to HEC. In 2023 alone, 433 elephants and 145 humans lost their lives, setting a grim record. The human death rate from HEC has surged by 42% over the past three decades. Approximately 69.4% of the elephant’s range overlaps with human settlements, particularly in the lowland dry zone, where 59.9% of elephants are concentrated. This overlap exacerbates conflicts, with elephants raiding crops like sugarcane, rice, and bananas, leading to property damage and retaliatory killings by farmers.

Causes of Human-Elephant Conflict

The root causes of HEC in Sri Lanka are multifaceted:

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Forest cover has dwindled from 70% of Sri Lanka’s land area in the 19th century to less than 22% today, driven by agricultural expansion, settlements, and infrastructure development. This has confined elephants to smaller, fragmented habitats, disrupting their migratory routes.

- Crop Raiding: Elephants are attracted to palatable crops, leading to frequent raids on farmlands. Traditional slash-and-burn agriculture once created ideal elephant habitats, but permanent cultivation has reduced available foraging areas, pushing elephants into human territories.

- Population Growth: Sri Lanka’s human population has grown from 2.5 million in the 19th century to 21.6 million today, increasing pressure on land resources and intensifying competition with elephants.

- Problem Elephants: Certain elephants, often young males, become habitual crop raiders or exhibit aggressive behavior, escalating conflicts.

These factors have rendered HEC a significant conservation, socio-economic, and environmental challenge, with 16 of Sri Lanka’s 24 districts reporting incidents.

Government Planning and Conservation Strategies

The Sri Lankan government, through the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC), has implemented several strategies to mitigate HEC and conserve elephants, though challenges in implementation persist. Key initiatives include:

1. National Policy for Elephant Conservation and Management

Adopted in 2020, this policy aims to manage elephants in situ, recognizing that confining them to protected areas is unsustainable, as only 18.4% of their range lies within national parks like Yala, Wilpattu, Udawalawe, and Minneriya. The policy promotes coexistence through:

- Electric Fencing: Installing and maintaining low-cost, battery-powered electric fences to deter elephants from entering villages and farmlands. These fences deliver mild shocks, ensuring minimal harm.

- Wildlife Corridors: Establishing corridors to connect fragmented habitats, allowing safe elephant movement. For example, the Udawalawe Elephant Research Project monitors elephant movements to inform corridor planning.

- Compensation Schemes: Providing financial compensation for human deaths, injuries, and property damage caused by elephants. While this scheme exists, delays and inadequate payouts have limited its effectiveness.

Despite its comprehensive framework, the policy’s implementation has been hampered by funding shortages and staffing deficits. The DWC operates with only one-sixth of the required workforce, undermining enforcement and monitoring efforts.

2. Protected Areas and Holding Grounds

Sri Lanka has 26 national parks, but many are too small (less than 1,000 km²) to encompass elephants’ home ranges, which can exceed 41 km² per individual. The government has attempted to relocate elephants to “holding grounds” like Horowpathana National Park, but these have faced criticism. Of the 65 elephants relocated to Horowpathana, 16 died within six years due to malnutrition, and others were killed while attempting to escape, highlighting mismanagement and insufficient resources.

3. Elephant Census and Research

In August 2024, the DWC conducted the first nationwide elephant census since 2011, using the “waterhole counting” method, with thousands of volunteers monitoring watering holes. The results, expected by late 2024, will provide updated population data to guide conservation planning. Partnerships with organizations like the Elephant Forest and Environment Conservation Trust (EFECT) and the Udawalawe Elephant Research Project enhance data collection on elephant behavior, health, and migration patterns.

4. Legal Protections

The Sri Lankan elephant is protected under national law, with killing an elephant carrying the death penalty. The species is also listed on CITES Appendix I, prohibiting international trade. However, enforcement remains weak, particularly against illegal activities like the use of “jaw bombs” (explosives hidden in food) by farmers to deter elephants.

People Awareness and Community-Based Initiatives

Raising public awareness and engaging communities are critical to reducing HEC and fostering coexistence. Several initiatives are underway:

1. Community-Based Conservation

Organizations like the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS) and the Centre for Conservation and Research work with local communities to promote sustainable coexistence. For example:

- Community Fences: In Anuradhapura, the Uga Ulagalla hotel collaborated with conservationists to install community-maintained electric fences, reducing crop raids while empowering locals.

- Regenerative Agro-Ecology: Projects encourage farmers to grow elephant-deterrent crops like oranges, which create natural barriers and reduce conflict. The International Elephant Project supports such initiatives to promote biodiversity and sustainable farming.

2. Education and Outreach

Conservation groups conduct workshops and school programs to educate rural communities about elephant behavior and safety measures, such as avoiding confrontation during crop raids. The SLWCS engages villagers in 12 communities near Wasgamuwa National Park, fostering leadership and conservation awareness.

3. Ecotourism and Economic Incentives

Ecotourism generates revenue for conservation and provides economic benefits to communities. National parks attract tourists eager to observe elephants, and ethical sanctuaries like the Pinnawala Elephant Orphanage and Millennium Elephant Foundation offer opportunities to learn about conservation. However, controversies over animal welfare in some facilities underscore the need for ethical practices.

4. Volunteer and Research Programs

The Sri Lanka Elephant Project, a collaboration between the Oklahoma City Zoo and the University of Peradeniya, involves local students in research and conservation, building capacity for future conservationists. Volunteer programs, such as those run by The Mighty Roar and Pod Volunteer, engage international and local participants in monitoring elephants and supporting community projects.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite these efforts, significant challenges remain. The DWC’s understaffing and funding constraints limit the scalability of conservation programs. Climate change exacerbates the crisis by altering rainfall patterns and reducing fertile land, forcing elephants into human areas for food and water. Infrastructure development, such as the Moragahakanda Dam, has reduced grasslands, intensifying HEC in areas like Minneriya.

To address these issues, experts like Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando advocate for:

- Strengthened Policy Implementation: Fully funding and staffing the 2020 National Policy to ensure effective execution.

- Innovative Solutions: Expanding regenerative agro-ecology and exploring non-lethal deterrents like bioacoustic devices to repel elephants.

- Public-Private Partnerships: Collaborating with hotels, NGOs, and international organizations to fund conservation and awareness campaigns.

- Data-Driven Conservation: Using the 2024 census results to prioritize conflict hotspots and tailor mitigation strategies.

Conclusion

The Sri Lankan elephant’s survival hinges on balancing conservation with human needs in a densely populated island nation. With nearly 70% of their range shared with humans, coexistence is the only viable path forward. Government strategies like electric fencing, wildlife corridors, and compensation schemes, combined with community-driven initiatives and public awareness campaigns, offer hope. However, overcoming funding shortages, staffing deficits, and climate challenges requires urgent action. By fostering collaboration between policymakers, conservationists, and communities, Sri Lanka can protect its elephants, ensuring they remain a vibrant part of its natural and cultural heritage for generations to come.

Sources: