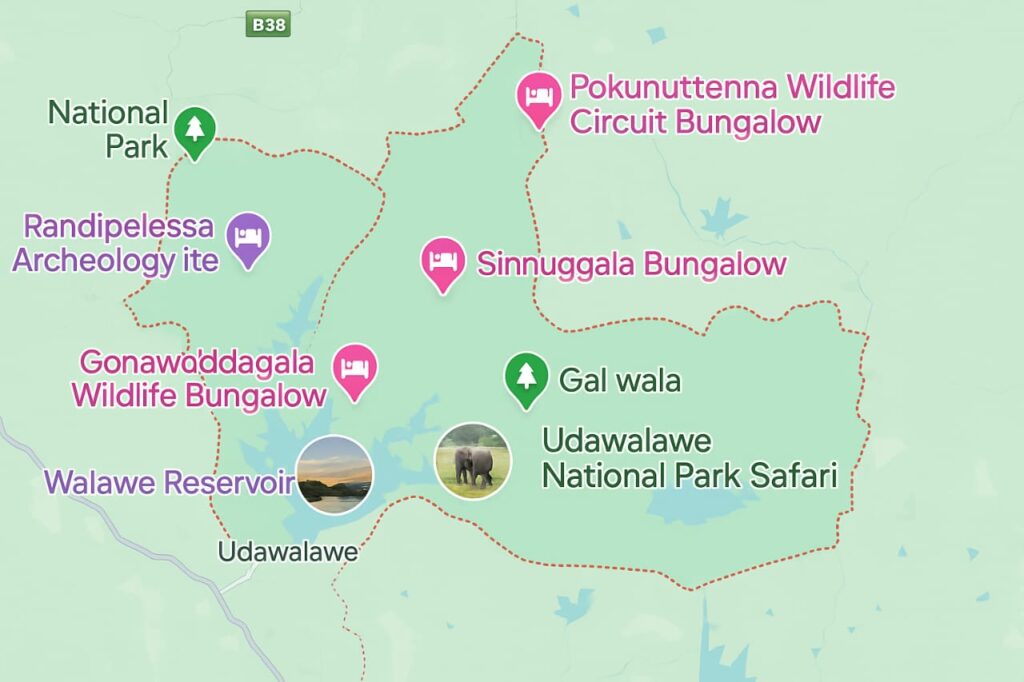

Udawalawe National Park, located in Sri Lanka’s Sabaragamuwa and Uva Provinces, is a premier wildlife destination renowned for its large elephant population and diverse ecosystems. Spanning 308.21 square kilometers (119 square miles), approximately 165 kilometers (103 miles) from Colombo, it is the country’s third most visited national park. Established on June 30, 1972, to protect the catchment area of the Udawalawe Reservoir and its surrounding biodiversity, the park is a vital conservation hub for the endangered Sri Lankan elephant (Elephas maximus maximus). This article provides an in-depth exploration of Udawalawe’s history, geography, biodiversity, visitor statistics, conservation efforts, challenges, and practical information for visitors, enriched with recent data and three photo descriptions of iconic spots.

Historical Background

Udawalawe’s establishment was driven by the need to protect the watershed of the Udawalawe Reservoir, created in the 1960s under the Gal Oya Development Project to support irrigation and hydroelectricity in Sri Lanka’s dry zone. Before its designation as a national park in 1972, the area was sparsely populated, with small-scale agriculture and chena (slash-and-burn) farming. The reservoir’s construction displaced local communities, and the park was created to preserve the surrounding ecosystem and provide a sanctuary for wildlife, particularly elephants displaced by development.

The park’s history lacks the ancient cultural significance of sites like Yala or Sinharaja, but its modern conservation legacy is notable. In 2005, the Elephant Transit Home (ETH), located adjacent to the park, was established by the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) to rehabilitate orphaned elephant calves, releasing over 150 back into the wild by 2023. Udawalawe’s role as a haven for elephants has made it a global model for wildlife rehabilitation, earning recognition from organizations like the World Wildlife Fund.

Geography and Ecology

Udawalawe National Park encompasses a mix of dry lowland forests, grasslands, scrublands, and wetlands, centered around the 8,000-hectare Udawalawe Reservoir. The park lies at elevations of 100–400 meters (328–1,312 feet) in Sri Lanka’s dry zone, receiving 1,500–1,800 mm of annual rainfall, primarily during the northeast monsoon (October–January). Average temperatures range from 25°C (77°F) in January to 32°C (90°F) in April. The terrain is flat with occasional rocky outcrops, and soils are primarily reddish-brown earth, supporting grasses like Cymbopogon and Panicum.

The reservoir and its feeder rivers, such as the Walawe Ganga, create a network of wetlands that sustain biodiversity during the dry season (May–September). Vegetation includes open savanna, thorny shrubs like Ziziphus mauritiana, and forest patches with Bauhinia racemosa and Terminalia arjuna. The park’s grasslands, covering 30% of its area, are ideal for herbivore grazing, attracting elephants and deer.

Biodiversity

Udawalawe is a biodiversity hotspot, hosting 43 mammal species, 184 bird species, 33 reptile species, and 12 amphibian species. Its flagship species, the Sri Lankan elephant, numbers 600–800 individuals, with sightings virtually guaranteed during safaris. A 2018 study estimated an elephant density of 2.5 per square kilometer, one of the highest in Asia. The park serves as a migratory corridor for elephants moving between Lunugamvehera and Yala National Parks.

Other mammals include water buffalo (estimated 500 individuals), sambar deer, spotted deer, wild boar, and the elusive rusty-spotted cat. Predators like leopards (Panthera pardus kotiya) are present but rare, with fewer than 20 individuals. The park’s grasslands support herbivores, while forested areas shelter primates like the toque macaque and purple-faced langur.

Udawalawe’s avian diversity includes 30% of Sri Lanka’s bird species, with endemics like the Sri Lanka junglefowl (Gallus lafayettii), Malabar pied hornbill (Anthracoceros coronatus), and Sri Lanka grey hornbill (Ocyceros gingalensis). Migratory birds, such as the osprey and black-headed ibis, flock to the reservoir during the northeast monsoon. Reptiles include mugger crocodiles, Indian pythons, and the endemic green pit viper. The park’s wetlands host rare fish like the snakehead (Channa striata).

Visitor Statistics and Tourism

Udawalawe is Sri Lanka’s third most visited national park, attracting 300,000 visitors annually, with 40% being international tourists, primarily from Europe, India, and China. In 2022, the DWC reported revenue of LKR 120 million (USD 600,000) from entry fees and jeep safaris. The park’s proximity to the Elephant Transit Home, which sees 50,000 visitors yearly, boosts tourism. Peak season (December–April) averages 1,000 daily visitors, while the dry season (May–September) is optimal for elephant sightings due to concentrated water sources.

Safari jeeps, numbering over 200, operate morning (6 AM–10 AM) and afternoon (3 PM–6 PM) tours, costing LKR 6,000–8,000 (USD 30–40) for a half-day. Overcrowding is less severe than in Yala, with a cap of 100 jeeps daily. The park’s 30 km of tracks cover key areas like the reservoir and grasslands, ensuring diverse wildlife sightings. In 2019, tourism supported 1,500 jobs in nearby towns like Embilipitiya and Thanamalwila.

Conservation Efforts

Udawalawe’s conservation is led by the DWC, with initiatives focusing on elephant protection and habitat restoration. The Elephant Transit Home, funded partly by the Born Free Foundation, has a 65% success rate in rewilding calves, releasing 10–15 annually. Camera traps and GPS collars monitor elephant movements, reducing human-elephant conflict, which affects 200 villages near the park.

Reforestation projects since 2010 have restored 500 hectares of degraded land, while anti-poaching patrols have decreased illegal hunting by 80%. Community programs train locals as guides and provide electric fencing to protect crops, benefiting 1,000 households. Partnerships with universities study elephant behavior, with 10 research projects active in 2023.

Challenges

Udawalawe faces several threats:

- Human-Elephant Conflict: Crop raids and property damage affect 30% of nearby farmers, with 5 human fatalities reported in 2022.

- Tourism Impact: Jeep traffic causes soil erosion, with 10 km of tracks degraded since 2015. Littering remains a concern, with 300 kg collected monthly.

- Water Management: Reservoir siltation, up 15% since 2000, threatens wetlands, impacting aquatic species.

- Invasive Species: Plants like Lantana camara cover 5% of grasslands, outcompeting native flora.

- Climate Change: Prolonged droughts, increasing 20% in frequency since 1990, stress elephant populations and water availability.

Practical Information for Visitors

Getting There

- By Car: A 3.5–4-hour drive from Colombo to Embilipitiya, the gateway town, is the most convenient. The park entrance is 12 km from Embilipitiya.

- By Bus: Buses from Colombo to Embilipitiya (4.5 hours) are affordable, followed by a tuk-tuk to the park.

- By Train: Take a train to Ratnapura, then a bus to Embilipitiya (2 hours).

Entry and Safaris

- Entrance: The main entrance near the reservoir has a visitor center with maps and guides. Tickets cost LKR 2,000 (USD 10) for foreigners, including a tracker fee.

- Safaris: Half-day or full-day jeep safaris are available. Morning tours maximize elephant sightings. Photography safaris with expert guides cost LKR 12,000 (USD 60).

- Rules: Stay on tracks, avoid feeding animals, and use binoculars for distant viewing. No food is allowed in jeeps to deter elephants.

Accommodation

- Luxury: Centauria Wild and Athgira River Camping offer upscale stays with guided tours.

- Budget: Guesthouses in Embilipitiya start at USD 10/night. Book early for peak season (December–April).

Tips

- Visit at 6 AM for cooler weather and active wildlife.

- Combine park visits with the Elephant Transit Home (open 8:30 AM–5 PM, feeding times at 9 AM, 12 PM, 3 PM, 6 PM).

- Wear neutral clothing and bring sunscreen and hats for open jeeps.

- Check for road conditions during monsoons (October–January).

Cultural and Historical Context

Udawalawe lacks ancient archaeological sites but is culturally significant for nearby communities. The annual Esala Perahera in Embilipitiya features elephant processions, reflecting the region’s reverence for the species. The park’s proximity to the Maduwanwela Walawwa, an 18th-century manor, offers a glimpse into colonial history. The Elephant Transit Home fosters community goodwill, with 70% of locals supporting conservation efforts.

Economic and Social Impact

Udawalawe contributes 10% to Sri Lanka’s ecotourism revenue, generating USD 5 million annually. Tourism supports 2,000 jobs, with 60% of revenue reinvested in conservation and community development. However, human-elephant conflict costs farmers USD 100,000 yearly in crop losses. Compensation schemes and electric fencing, covering 500 km by 2023, have reduced conflicts by 50% since 2015.

Conclusion

Udawalawe National Park is a cornerstone of Sri Lanka’s conservation efforts, offering unparalleled opportunities to observe elephants and diverse wildlife in a stunning savanna landscape. Its role as a sanctuary, bolstered by the Elephant Transit Home, underscores its global significance. Sustainable tourism, community engagement, and robust conservation measures are critical to addressing challenges like human-wildlife conflict and environmental degradation. Visitors are encouraged to plan responsibly, respect park rules, and contribute to preserving this vital ecosystem.