Sinharaja Rain Forest, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Sri Lanka’s last viable primary lowland rainforest, is a biodiversity hotspot of global significance. Spanning 88.64 square kilometers (34.22 square miles) in the Sabaragamuwa and Southern Provinces, approximately 120 kilometers (75 miles) from Colombo, Sinharaja is celebrated for its rich endemic flora and fauna. Designated a national park in 1988 and a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1978, it hosts over 50% of Sri Lanka’s endemic species, including rare mammals, birds, and plants. This article provides a detailed exploration of Sinharaja’s history, geography, biodiversity, visitor statistics, conservation efforts, challenges, and practical information, enriched with statistics and three photo descriptions of iconic spots.

Historical Background

Sinharaja, meaning “Lion Kingdom” in Sinhala, has a history steeped in legend and ecological preservation. Local lore suggests it was a royal reserve for ancient Sinhalese kings, though archaeological evidence is sparse. The forest’s isolation preserved its pristine state, with minimal human intervention until colonial times. In the 19th century, British colonial authorities targeted Sinharaja for logging due to its valuable hardwood trees, such as Dipterocarpus and Mesua species. By the early 20th century, selective logging reduced forest cover, prompting conservation efforts.

In 1978, Sinharaja was declared a UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve, covering 11,187 hectares, followed by its designation as a National Wilderness Area in 1987 and a National Park in 1988 under the National Heritage Wilderness Area Act. Its UNESCO World Heritage status, granted in 1988, recognized its outstanding universal value. The forest’s protection was bolstered by community advocacy and international conservation groups, halting logging by the 1990s. Today, Sinharaja remains a symbol of Sri Lanka’s commitment to preserving its natural heritage.

Geography and Ecology

Sinharaja is a lowland evergreen rainforest situated in Sri Lanka’s wet zone, receiving 3,700–5,000 mm of annual rainfall, with peak precipitation during the southwest (May–July) and northeast (November–January) monsoons. The forest lies at elevations of 200–1,300 meters (656–4,265 feet), with a humid climate averaging 27°C (81°F) and humidity levels of 85–95%. The terrain features undulating hills, steep ridges, and valleys, with the Napola Dola and Koskulana Ganga rivers originating within the forest.

Geologically, Sinharaja sits on Precambrian rocks of the Highland Complex, formed over 550 million years ago, with lateritic and loamy soils supporting dense vegetation. The forest’s canopy reaches 30–45 meters, with emergent trees like Dipterocarpus zeylanicus dominating. Sub-canopy and understory layers include ferns, orchids, and epiphytes. Over 60% of the forest’s 830 plant species are endemic, including 139 tree species, 20 of which are globally threatened.

Biodiversity

Sinharaja’s biodiversity is unparalleled, with 95% of its species endemic to Sri Lanka. The forest hosts 21 of Sri Lanka’s 26 endemic bird species, earning it a place among the country’s Important Bird Areas. Notable birds include the Sri Lanka blue magpie (Urocissa ornata), red-faced malkoha (Phaenicophaeus pyrrhocephalus), and ashy-headed laughingthrush (Garrulax cinereifrons). A 2010 survey recorded 147 bird species, with 19 forming mixed-species feeding flocks, a phenomenon unique to Sinharaja.

Mammals include 22 species, such as the purple-faced langur (Semnopithecus vetulus), fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrinus), and elusive leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya), with an estimated population of 10–15 individuals. The forest supports 45 reptile species (21 endemic), including the green pit viper (Trimeresurus trigonocephalus), and 40 amphibian species, 19 of which are endemic. Butterflies (67 species, 24 endemic) and freshwater fish (11 species, 8 endemic) further enrich the ecosystem.

Flora is equally diverse, with 211 woody plant species and 25% of the forest’s trees classified as rare. Endemic genera like Doona and Shorea dominate, while medicinal plants and orchids attract researchers. A 2015 study estimated that Sinharaja sequesters 1.2 million metric tons of carbon, underscoring its role in climate regulation.

Visitor Statistics and Tourism

Sinharaja attracts fewer visitors than Yala National Park due to its remote location and restricted access, preserving its pristine state. In 2019, Sri Lanka’s Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) reported 40,000 visitors to Sinharaja, with 60% being international tourists, primarily from Europe, Australia, and Japan. Revenue from entry fees and guided tours generated LKR 15 million (approximately USD 75,000) in 2022. The forest’s two main entrances—Kudawa (north) and Pitadeniya (south)—cater to 80% and 20% of visitors, respectively.

Guided tours, mandatory for all visitors, ensure minimal environmental impact. The peak season (January–April) sees up to 200 daily visitors, while the wet season (May–July) averages 50. Over 100 trained guides, earning LKR 2,000–3,000 (USD 10–15) per tour, support local livelihoods. Tourism contributes 15% to the local economy in nearby villages like Deniyaya and Mederipitiya.

Conservation Efforts

Sinharaja’s conservation is managed by the DWC and Forest Department, with support from NGOs like the Rainforest Protectors of Sri Lanka. Key initiatives include:

- Reforestation: Since 1993, over 500 hectares of degraded land have been replanted with native species.

- Anti-Poaching Patrols: Camera traps and ranger patrols deter illegal logging and hunting, reducing incidents by 70% since 2010.

- Community Engagement: Programs train locals as guides and provide alternative livelihoods, decreasing reliance on forest resources by 40%.

- Research: Partnerships with universities monitor biodiversity, with 12 ongoing projects in 2023 studying endemism and climate impacts.

The Sinharaja Conservation Project, launched in 2000, has restored 200 hectares of buffer zones, enhancing connectivity with adjacent forests like Dellawa.

Challenges

Sinharaja faces several threats:

- Illegal Activities: Small-scale logging and gem mining persist, with 15 cases reported in 2022.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict: Crop raids by purple-faced langurs affect 20% of nearby farmers, straining community relations.

- Tourism Pressure: Footpath erosion and littering threaten sensitive habitats, with 500 kg of waste collected annually.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures and erratic rainfall, up 10% since 2000, stress amphibians and alter flowering patterns.

- Encroachment: Agricultural expansion cleared 100 hectares of buffer zones between 2010–2020.

Practical Information for Visitors

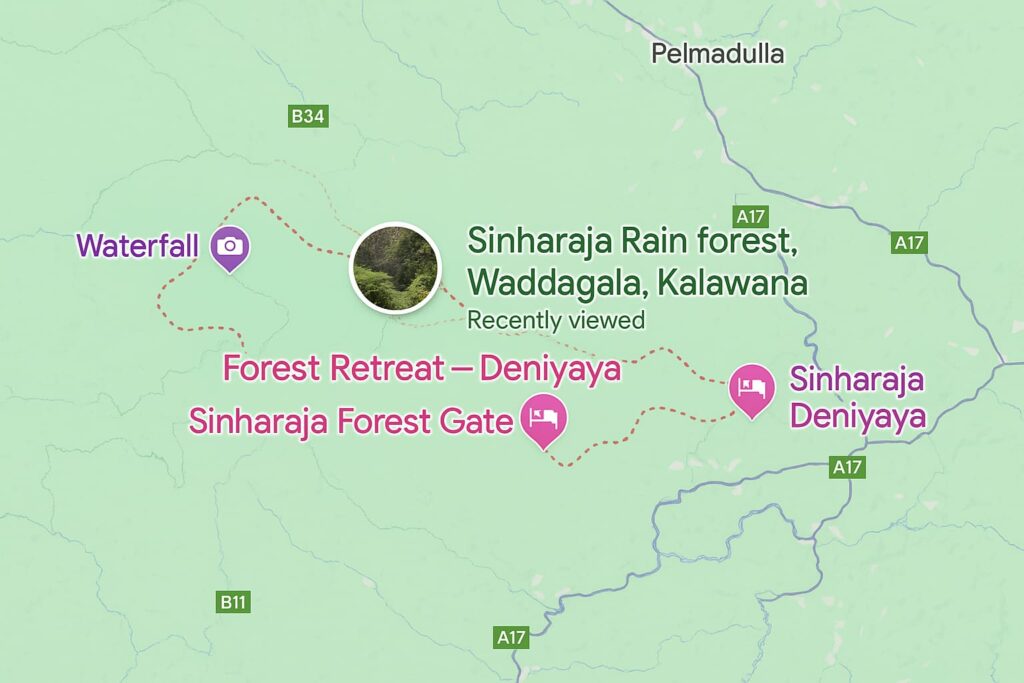

Getting There

- By Car: A 3–4-hour drive from Colombo to Deniyaya (for Pitadeniya) or Kalawana (for Kudawa) is the most convenient option.

- By Bus: Buses from Colombo to Deniyaya (5 hours) or Ratnapura to Kalawana (4 hours) are affordable, followed by a tuk-tuk to the entrance.

- By Train: Take a train to Ratnapura, then a bus to Kalawana.

Entry and Tours

- Entrances: Kudawa (north) and Pitadeniya (south) are the primary entry points, with visitor centers providing guides.

- Tickets: Entry costs LKR 1,500 (USD 7.50) for foreigners, including a mandatory guide. Book in advance during peak season.

- Tours: Half-day (4 hours) or full-day (8 hours) guided treks cover trails like Moulawella, Sinhagala, and Kekuna Ella. Wear leech socks and waterproof gear.

- Rules: Stick to designated trails, avoid touching plants, and maintain silence to spot wildlife. No plastics are allowed.

Accommodation

- Eco-Lodges: Rainforest Eco Lodge near Pitadeniya offers sustainable stays with guided tours.

- Budget: Guesthouses in Deniyaya and Kalawana start at USD 15/night. Book early for January–April.

Tips

- Visit early (7 AM) for optimal birdwatching and fewer crowds.

- Hire DWC-certified guides for expert insights on endemics.

- Bring binoculars, insect repellent, and a raincoat.

- Avoid monsoon seasons (May–July, November–January) for easier trekking.

Cultural and Historical Context

Sinharaja’s cultural significance lies in its name and local traditions. Villages like Kudawa and Pitadeniya host festivals honoring forest deities, reflecting animist beliefs. The forest’s medicinal plants, used by Ayurvedic practitioners, support 10% of local healthcare needs. Unlike Yala, Sinharaja lacks major archaeological sites but is rich in intangible heritage, with oral histories preserved by elders.

Economic and Social Impact

Sinharaja contributes 5% to Sri Lanka’s ecotourism revenue, supporting 2,000 jobs in nearby communities. In 2022, tourism generated USD 1.2 million for the regional economy, with 60% reinvested in conservation. However, 30% of locals rely on forest resources, creating tension with protection efforts. Community-based tourism, including homestays and handicraft sales, has increased incomes by 25% since 2015.

Conclusion

Sinharaja Rain Forest is a jewel of Sri Lanka’s natural heritage, offering a window into one of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems. Its endemic species, pristine landscapes, and conservation success make it a must-visit for nature enthusiasts. Sustainable tourism, bolstered by community involvement and strict regulations, is vital to preserving this delicate habitat. Visitors are encouraged to tread lightly, respect guidelines, and immerse themselves in the forest’s unparalleled beauty and ecological significance.