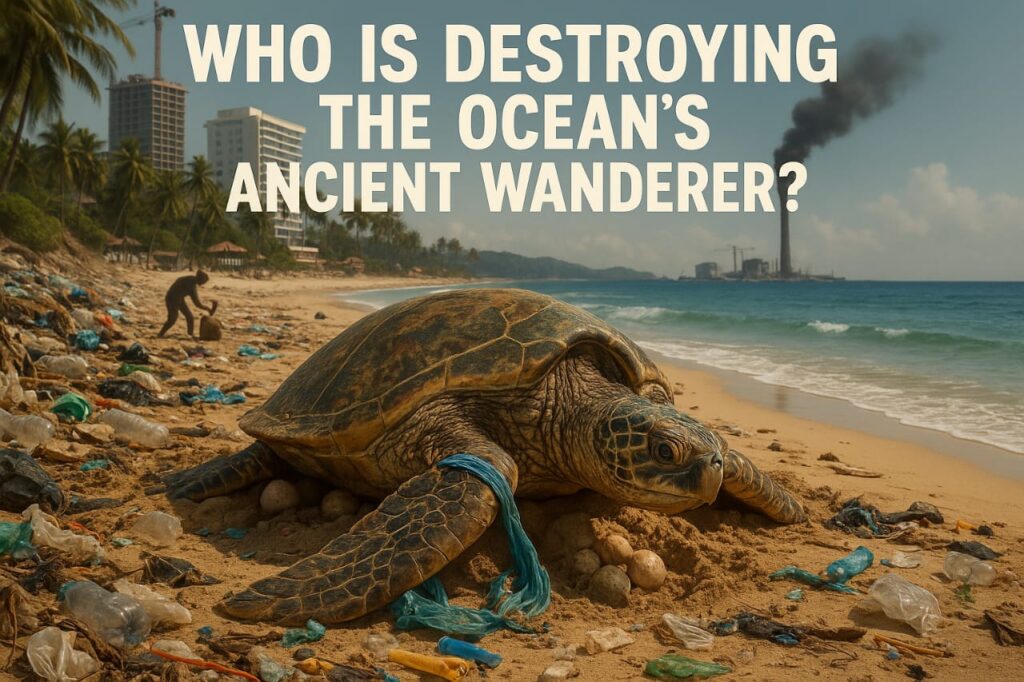

Sri Lanka, an island nation surrounded by the warm waters of the Indian Ocean, is a critical habitat for five of the world’s seven sea turtle species: the green turtle (Chelonia mydas), hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta), olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea), and leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). These ancient mariners, revered in Sri Lankan culture and vital to marine ecosystems, face severe threats from coastal development, illegal egg poaching, and marine pollution. All five species are listed as endangered or critically endangered by the IUCN. This article explores the challenges confronting Sri Lanka’s sea turtles, provides key statistics, details government and conservation efforts, and highlights initiatives to raise public awareness for their protection.

The Crisis in Numbers: Key Statistics

Sri Lanka’s southern and southwestern coasts, particularly beaches like Rekawa, Kosgoda, and Bentota, are among the world’s most important sea turtle nesting sites. However, sea turtle populations have declined dramatically. The Turtle Conservation Project (TCP) estimates that nesting numbers have dropped by 50% since the 1980s, with fewer than 10,000 nests recorded annually across the country. The green turtle, the most common species, accounts for 60% of nests, followed by the olive ridley (25%) and hawksbill (10%).

Illegal egg collection remains a significant threat, with an estimated 80% of nests historically raided before conservation efforts intensified in the 1990s. Today, poaching affects 10-15% of nests, despite legal protections. Bycatch in fishing nets claims approximately 5,000-7,000 turtles annually, according to the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA). Marine plastic pollution is another growing concern, with 70% of necropsied turtles showing plastic ingestion, contributing to a 20% mortality rate among juveniles. Coastal development has reduced nesting beaches by 30% since the 1970s, particularly in tourist-heavy areas like Hikkaduwa.

Threats to Sri Lanka’s Sea Turtles

The primary threats to sea turtles in Sri Lanka include:

- Illegal Egg Poaching: Despite bans, turtle eggs are still harvested for local consumption and sale, driven by poverty and cultural misconceptions about their nutritional value.

- Bycatch in Fisheries: Turtles are accidentally caught in gillnets and trawlers, often drowning or suffering severe injuries. Small-scale fisheries account for 65% of bycatch incidents.

- Marine Pollution: Plastic debris, oil spills, and chemical runoff entangle turtles or are ingested, causing internal injuries and starvation. Sri Lanka generates 1.5 million tons of plastic waste annually, much of which enters the ocean.

- Habitat Loss: Coastal development, including hotels, roads, and artificial lighting, disrupts nesting sites and disorients hatchlings, reducing their survival rates from 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 2,000.

- Climate Change: Rising sea levels and warmer sand temperatures alter sex ratios (favoring females) and inundate nests, with 15% of nests lost to erosion in 2023.

These threats collectively undermine sea turtle populations and the health of marine ecosystems, where turtles maintain seagrass beds and coral reefs by grazing and dispersing nutrients.

Government Conservation Efforts

The Sri Lankan government, through the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) and the Coast Conservation Department (CCD), has implemented several measures to protect sea turtles, though enforcement and funding challenges persist. Key initiatives include:

1. National Sea Turtle Conservation Policy

Introduced in 2005 and updated in 2018, this policy aims to protect nesting beaches and reduce turtle mortality. It includes:

- Protected Nesting Sites: Designating key beaches like Rekawa and Kosgoda as sanctuaries, with restricted access during nesting season (April to September).

- Bycatch Reduction: Promoting turtle excluder devices (TEDs) in fishing nets, though adoption remains low, with only 10% of trawlers using TEDs as of 2024.

- Beach Monitoring: Deploying rangers to patrol nesting sites and deter poachers, though understaffing limits coverage to 50% of critical beaches.

2. Hatchery Programs

The DWC supports community-run hatcheries, where eggs from vulnerable nests are relocated to protected enclosures to prevent poaching and predation. In 2023, 120 hatcheries released 1.2 million hatchlings, a 30% increase from 2010. However, some hatcheries face criticism for improper handling, which can reduce hatchling survival rates.

3. Legal Protections

Sea turtles are protected under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance and the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act, with penalties for egg poaching and turtle killing including up to two years in prison and fines of LKR 50,000 (USD 165). All five species are listed on CITES Appendix I, prohibiting international trade. Enforcement, however, is inconsistent, with only 20% of reported poaching cases prosecuted between 2020 and 2023.

4. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

Sri Lanka has established MPAs like the Bar Reef Sanctuary and Pigeon Island National Park to safeguard turtle foraging grounds. The government plans to expand MPAs by 5% by 2030, though illegal fishing within these zones remains a challenge.

Conservation Initiatives by NGOs and Communities

Non-governmental organizations and local communities are pivotal in sea turtle conservation, often filling gaps in government efforts:

1. Turtle Conservation Project (TCP)

Founded in 1993, TCP operates hatcheries and conducts research in Rekawa, Kosgoda, and Panama. Their community-based model employs former poachers as “nest protectors,” reducing poaching by 90% in Rekawa since 2000. TCP also monitors turtle health, tagging 500 turtles annually to track migration patterns.

2. Kosgoda Sea Turtle Conservation Project

This initiative runs one of Sri Lanka’s largest hatcheries, releasing 200,000 hatchlings annually. It also rehabilitates injured turtles, treating 150 individuals in 2023, with 80% successfully released. The project collaborates with NARA to study the impact of plastic pollution on turtles.

3. Beach Cleanups and Plastic Reduction

Organizations like the Marine Environment Protection Authority (MEPA) and Eco Wave Sri Lanka organize beach cleanups, removing 500 tons of plastic from nesting beaches in 2023. MEPA’s “Plastic-Free Coast” campaign promotes biodegradable alternatives, reducing plastic waste by 15% in targeted coastal communities.

4. Community Engagement

TCP and the Bio Conservation Society train fishermen to use TEDs and release entangled turtles, reducing bycatch by 25% in pilot areas like Negombo. Community-led eco-tourism, such as turtle-watching tours in Rekawa, generates income for 200 families, incentivizing conservation.

Raising Public Awareness

Public awareness is critical to reducing threats to sea turtles, particularly in coastal communities where cultural practices and economic pressures drive poaching. Key initiatives include:

1. Educational Programs

TCP and the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS) conduct workshops in schools and fishing villages, reaching 10,000 students and 2,000 fishermen annually. These programs dispel myths about turtle eggs and teach safe fishing practices, fostering a conservation ethic.

2. Media Campaigns

The “Save Our Turtles” campaign by MEPA, launched in 2022, uses TV, radio, and social media to highlight turtle conservation. With over 500,000 social media engagements, it has increased volunteer participation in beach cleanups by 40%. Documentaries like Turtles of Sri Lanka by Derana TV have reached 2 million viewers since 2023.

3. Volunteer and Tourism Programs

International volunteer programs, such as those by Projects Abroad and The Mighty Roar, engage tourists in hatchery work and beach patrols, contributing USD 500,000 to conservation in 2023. Ethical turtle-watching tours educate visitors about turtle ecology, with 80% of participants reporting increased conservation awareness.

4. School and Community Events

Annual events like World Sea Turtle Day (June 16) feature beach cleanups, art competitions, and turtle releases, engaging 5,000 participants across 10 coastal towns in 2024. These events build community pride in protecting turtles as a national treasure.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite progress, sea turtle conservation faces significant obstacles:

- Funding Shortages: The DWC’s annual budget of LKR 4 billion allocates only 5% to marine conservation, limiting ranger training and hatchery support.

- Weak Enforcement: Illegal fishing and poaching persist due to inadequate patrolling, with only 30% of MPAs effectively monitored.

- Plastic Pollution: Sri Lanka’s waste management infrastructure struggles to handle 1.5 million tons of plastic annually, requiring systemic changes.

- Tourism Pressure: Unregulated turtle-watching tours and hatchery visits can disturb nesting sites, with 20% of nests in Hikkaduwa affected by artificial lighting in 2023.

To address these challenges, conservationists recommend:

- Increased Funding: Allocating 10% of coastal tourism revenue to turtle conservation.

- Stricter Regulations: Enforcing TED use in 50% of fisheries by 2030 and banning single-use plastics in coastal zones.

- Technology Integration: Using drone surveillance to monitor nesting beaches and detect illegal activities.

- Regional Cooperation: Collaborating with India and the Maldives to protect migratory routes, as 30% of Sri Lanka’s turtles cross international waters.

Conclusion

Sri Lanka’s sea turtles, vital to marine ecosystems and cultural heritage, face an uncertain future amid poaching, pollution, and habitat loss. Government efforts like hatchery programs and MPAs, combined with NGO-led initiatives and community engagement, have made strides in protecting these marine marvels, with 1.2 million hatchlings released annually. Public awareness campaigns are shifting attitudes, encouraging coastal communities to view turtles as allies rather than resources. By addressing funding gaps, strengthening enforcement, and tackling plastic pollution, Sri Lanka can ensure its sea turtles continue to grace its shores, preserving a legacy of biodiversity for generations to come.

Sources:

- Turtle Conservation Project (TCP), Sri Lanka

- National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency (NARA)

- Marine Environment Protection Authority (MEPA)

- IUCN Red List, 2020

- Mongabay, 2023