Yala National Park, also known as Ruhunu National Park, is Sri Lanka’s most visited and second-largest national park, renowned for its rich biodiversity and high leopard density. Located in the island’s southeastern corner, it spans 979 square kilometers (378 square miles) across the Southern and Uva Provinces, approximately 300 kilometers (190 miles) from Colombo. Established as a wildlife sanctuary in 1900 and designated a national park in 1938, Yala is a cornerstone of Sri Lanka’s conservation efforts, protecting iconic species like the Sri Lankan leopard, elephant, and over 200 bird species. This article explores Yala’s history, geography, biodiversity, visitor statistics, conservation efforts, challenges, and practical information for visitors, supported by recent data and statistics.

Historical Background

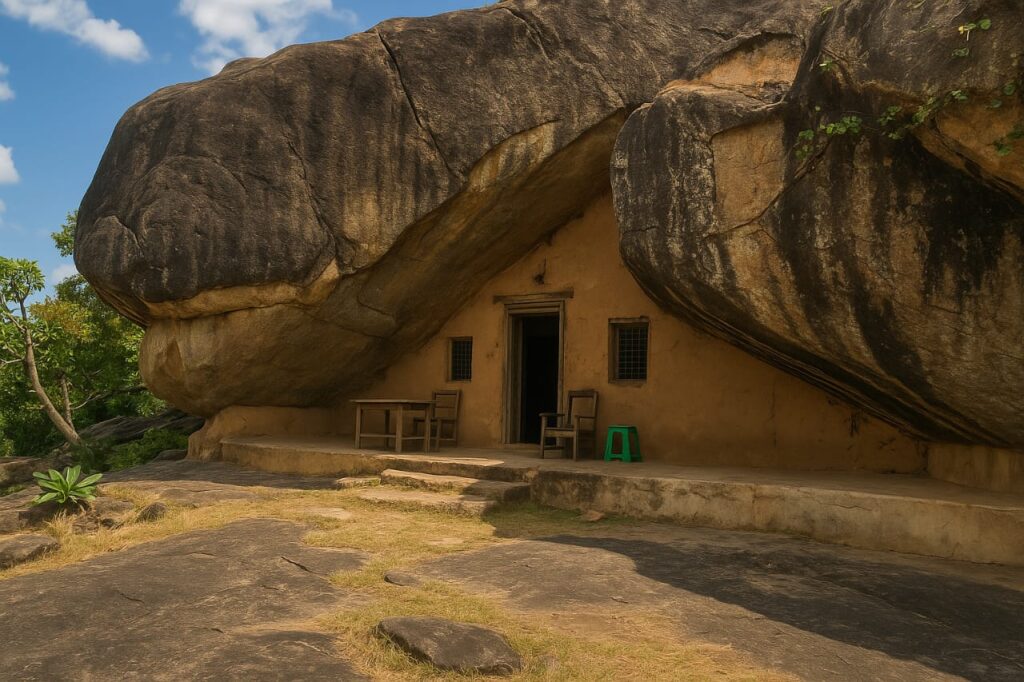

Yala’s history intertwines human civilization and natural preservation. The area hosted ancient civilizations, with archaeological sites like Sithulpawwa and Magul Vihara, two Buddhist pilgrimage sites within the park, dating back over 2,000 years. Sithulpawwa, a monastic settlement, reportedly housed 12,000 inhabitants seeking spiritual solace.

In 1560, Spanish cartographer Cipriano Sánchez noted Yala as “abandoned for 300 years due to insalubrious conditions.” In 1806, Chief Justice Sir Alexander Johnston documented the region’s potential after traveling from Trincomalee to Hambantota. On March 23, 1900, the British colonial government proclaimed Yala and Wilpattu as reserves under the Forest Ordinance, initially covering 389 square kilometers (150 square miles) between the Menik and Kumbukkan Rivers. The park was officially named a national park on March 1, 1938, under the Flora and Fauna Protection Ordinance, championed by D. S. Senanayake, the minister of agriculture.

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami devastated Yala’s coastal belt, claiming 250 lives and altering land features. Remarkably, no animals were reported harmed, prompting theories about their “sixth sense” or rapid response to environmental cues. A tsunami memorial at Patanangala beach serves as a reminder of this tragedy.

Geography and Ecology

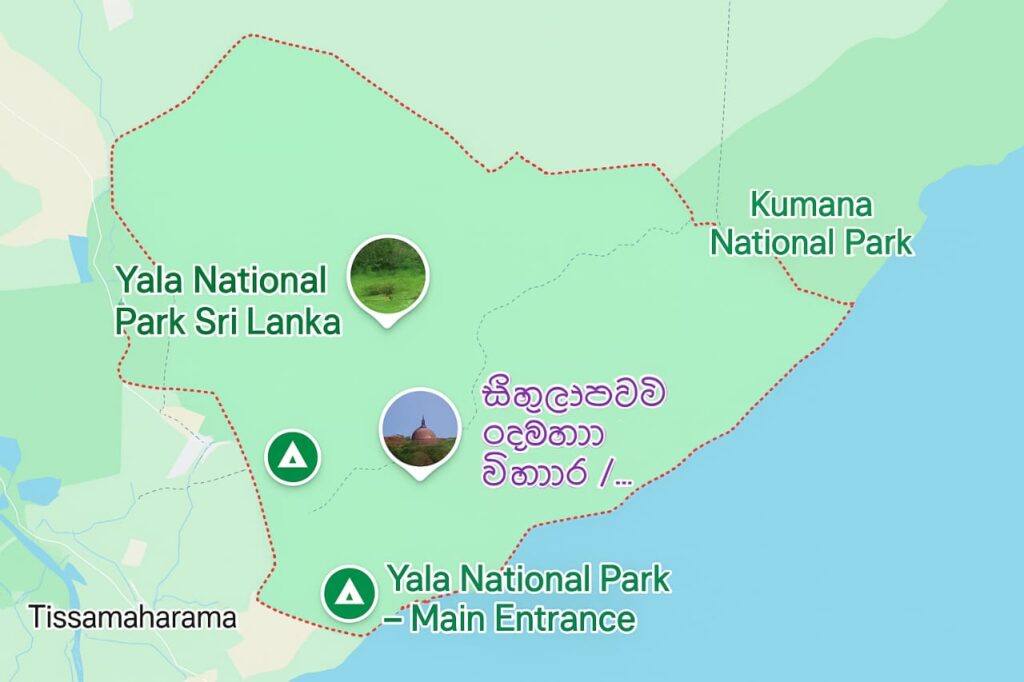

Yala National Park encompasses a diverse range of ecosystems, including monsoon forests, dry monsoon forests, thorn forests, grasslands, freshwater and marine wetlands, and sandy beaches. The park is divided into five blocks, with Blocks I and V open to the public to preserve the natural habitat. Block I, also known as Ruhunu National Park, is the most visited, while Block III and the adjoining Kumana National Park (Yala East) are gaining popularity. The park’s total protected area, including adjoining sanctuaries like Lunugamvehera, covers nearly 130,000 hectares.

Geologically, Yala is composed of Precambrian metamorphic rock, classified into the Vijayan and Highland series, formed over 600 million years ago. The terrain is a flat, mildly undulating plain, with elevations ranging from 30 meters (98 feet) near the coast to 100–125 meters (328–410 feet) inland. Reddish-brown soil and low-humic grey soil dominate, supporting varied vegetation such as scrub jungle, mangroves, and Pitiya grasslands. Notable flora includes Drypetes sepiaria, Manilkara hexandra, Rhizophora mucronata, and Crinum zeylanicum.

The park lies in Sri Lanka’s semi-arid zone, with an annual precipitation of 898 mm, peaking during the northeast monsoon (October–December). November sees the highest rainfall (125 mm), while July is the driest. Average temperatures range from 28°C (82°F) in January to 30°C (86°F) in March. Wind speeds vary from 15 km/h during the northeast monsoon to 23 km/h during the southwest monsoon.

Biodiversity

Yala is a biodiversity hotspot, hosting 44 mammal species and 215 bird species, making it one of Sri Lanka’s 70 Important Bird Areas. The park is globally recognized for its leopard population (Panthera pardus kotiya), with one of the highest densities in the world. A 2001–2002 study in Block I estimated leopard density using a 92 km² study area, with observations over 237 days. The ongoing “Spotting the Spots” initiative uses visitor photographs to monitor leopard populations, similar to methods used in Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater.

The Sri Lankan elephant (Elephas maximus maximus) population is estimated at 250–300 individuals, often seen in small family groups or as solitary males. Elephants migrate through Lunugamvehera National Park to Udawalawe, with sightings peaking during the dry season (May–August). Other mammals include sloth bears, spotted deer, sambar, water buffalo, wild boar, golden jackals, and the rare rusty-spotted cat.

Yala’s avian diversity includes resident species like the jungle fowl, painted stork, and blue-faced malkoha, alongside migratory birds such as the northern pintail, white-winged tern, and lesser flamingo, which arrive during the northeast monsoon. Raptors like the crested serpent eagle and white-bellied sea eagle are also present. The park’s lagoons attract waterbirds, including pelicans, purple herons, and oriental darters.

Reptiles like crocodiles and land monitor lizards, along with amphibians and invertebrates, further enrich Yala’s ecosystem. The park’s coastal wetlands and freshwater tanks support a delicate balance of aquatic and terrestrial life.

Visitor Statistics and Tourism

Yala is Sri Lanka’s most popular national park, attracting both local and international visitors, with foreigners (especially Europeans) accounting for 30% of total visitors. In 2011, Sri Lanka recorded 855,975 tourist arrivals, with 198,536 visiting national parks (23%). Yala’s visitation exceeded 500,000 in 2012, with a record single-day count on February 13, 2013, of 1,000 foreign and 500 local visitors, generating revenue of LKR 2.6 million (approximately USD 20,000). In 2000, visitor income, including lodge fees, was USD 468,629, though revenue declined during periods of insecurity.

The park’s popularity has led to overcrowding, with over 250 safari jeeps operating, often causing traffic jams and disturbing wildlife. In 2013, it was estimated that 700 hotel rooms in the area, at 50% occupancy, could result in 120 daily park visitors from this segment alone. Safari drivers, earning LKR 4,000–5,000 (USD 30–40) per three-hour safari, are incentivized to prioritize leopard sightings, sometimes disregarding park rules.

The best time to visit is February to July, when low water levels draw animals to open areas. Morning (6 AM) and late afternoon (4 PM) safaris maximize wildlife sightings. The park typically closes in September and early October for maintenance, but no closure was announced for 2023.

Conservation Efforts

Yala’s conservation efforts focus on protecting its flagship species and mitigating human-wildlife conflict. Camera traps and GPS collars track leopard movements, while community-based initiatives engage locals in conservation. The Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) collaborates with organizations like the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society to enforce regulations and educate visitors.

The park’s management has introduced measures like monthly meetings with tour operators and educational materials to promote sustainable tourism. Plans for a new road aim to reduce congestion, but funding shortages and lax oversight of religious tourists visiting Sithulpawwa remain challenges.

Challenges

Yala faces several threats, including:

- Overcrowding: Excessive jeep traffic disrupts wildlife and degrades the visitor experience. Reports describe “traffic jams” with over 50 jeeps at park openings.

- Human-Wildlife Conflict: Elephants blocking roads and occasional leopard attacks highlight tensions between wildlife and humans.

- Poaching and Habitat Loss: Despite protections, illegal activities persist, threatening leopard and elephant populations.

- Mismanagement: The DWC has been criticized for prioritizing revenue over conservation, with inadequate regulation of safari operators.

- Environmental Degradation: Tourism-related soil erosion and littering impact ecosystems, exacerbated by unregulated religious tourism.

Practical Information for Visitors

Getting There

- By Car: A 4–5-hour drive from Colombo to Tissamaharama, the gateway town, is the most comfortable option. Hiring a driver allows flexibility.

- By Bus: A 6–7-hour bus ride from Colombo to Tissamaharama is budget-friendly, followed by a tuk-tuk to the park entrance.

- By Train: Take a train to Matara, then a bus or taxi to Tissamaharama.

Entry and Safaris

- Entrance: The main entrance is at Palatupana (Block I), with a visitor center providing information and trackers. Block III’s gate is on the Buttala-Kataragama Road, and Kumana’s is at Okanda.

- Tickets: Must be purchased at the entrance, including a tracker fee. Tipping trackers and drivers is customary.

- Safari Options: Morning, afternoon, or full-day jeep safaris are available. Early morning or late afternoon tours are best for wildlife viewing. Guided bush walks offer a closer look at smaller flora and fauna.

- Rules: Stay on designated tracks, avoid interacting with animals, and bring binoculars for better viewing. No food is allowed in jeeps to prevent elephant raids.

Accommodation

- Luxury: Hilton Yala Resort, located on the park’s edge, offers guided tours and modern amenities.

- Budget: Guesthouses and hotels in Tissamaharama cater to various budgets. Book in advance during peak season (January–July).

Tips

- Arrive at 6 AM to avoid crowds and increase sighting chances.

- Choose reputable safari operators prioritizing ethical wildlife viewing.

- Wear neutral clothing and avoid loud noises to minimize disturbance.

- Check weather forecasts, as November–December brings heavy rain.

Cultural and Historical Sites

Beyond wildlife, Yala offers cultural attractions:

- Sithulpawwa Temple: A restored rock temple accessible via separate roads from Tissamaharama or Kataragama, free of charge.

- Magul Vihara: An ancient Buddhist site reflecting Yala’s historical significance.

- Patanangala Tsunami Memorial: A poignant reminder of the 2004 disaster.

Economic and Social Impact

Yala significantly contributes to Sri Lanka’s economy through tourism. In 2011, national parks accounted for 23% of tourist visits, with Yala leading due to its leopard and elephant populations. However, the park’s popularity strains resources, and local communities face challenges from human-wildlife conflict. Conservation programs involving locals aim to balance economic benefits with environmental protection.

Conclusion

Yala National Park is a testament to Sri Lanka’s natural and cultural heritage, offering unparalleled opportunities to witness diverse wildlife in a stunning landscape. Its high leopard density, vibrant ecosystems, and historical sites make it a must-visit destination. However, sustainable tourism practices are critical to preserving its ecological integrity. By addressing overcrowding, enhancing conservation, and engaging local communities, Yala can continue to thrive as a global wildlife sanctuary. Visitors are encouraged to plan responsibly, respect park rules, and contribute to the preservation of this remarkable ecosystem.